Industry > Industrial Pyrmont

Industrial Pyrmont

Industry came slowly to Pyrmont until the 1870s, when quarries changed the landscape, sugar was shipped in to be refined, and trains brought wool and wheat to be stored and exported through Darling Harbour. Pyrmont became famously smoky, noisy and smelly. During two world wars, the pace was frenetic. From the 1950s onwards, however, old industries lost momentum. In the 1980s the State Government stepped in to launch a second wave of industry, based on clean, quiet, high-technology and high-rise apartments.

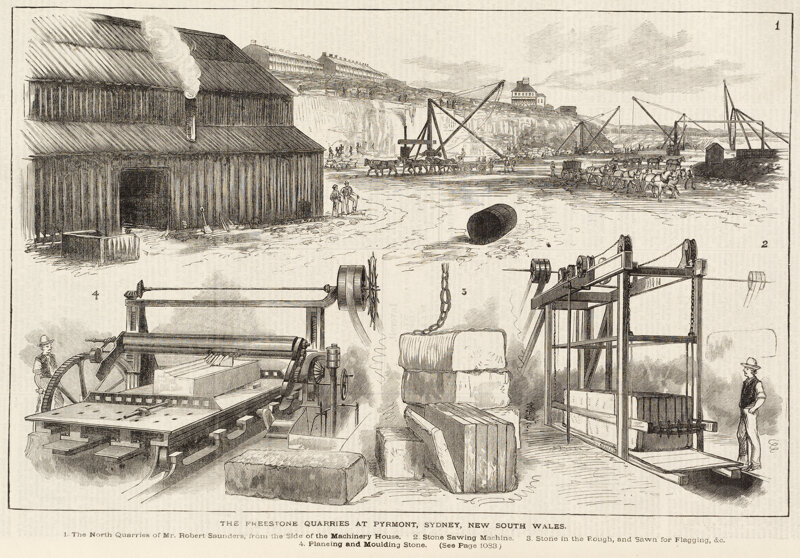

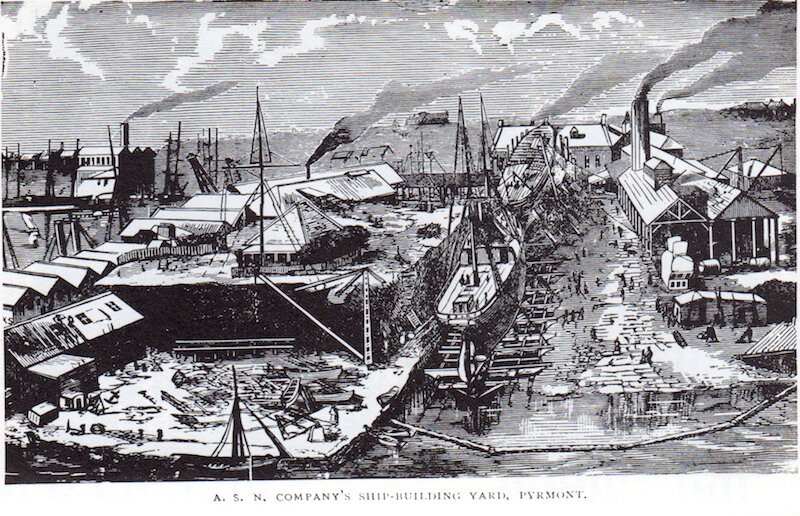

The peninsula remained rural and remote even after Pyrmont Bridge opened in 1858. The industries that did operate – shipbuilding and repairs, quarrying for ships’ ballast, iron works – were really maritime even if shore-based. When a journalist in 1870 visited “that stoniest of all stony-hearted suburbs, Pyrmont”, he reported that the City iron Works were “so shut out … that no one would dream of their existence save for vapour from smoke-shafts, and the clash and clang of heavy hammers.” (Illustrated Sydney News, 26 October 1870) The simple plant was “not designed for smelting metal from the ore - they make old iron into new.”

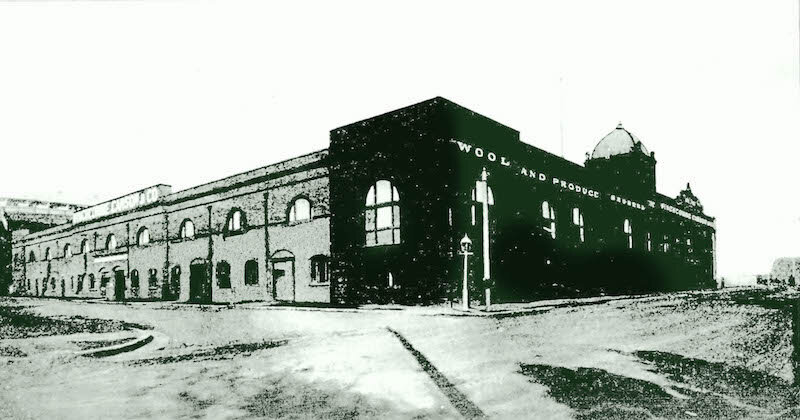

Darling Harbour railway station opened in 1875, another essentially maritime venture, bringing country produce to the harbour. Much more consequential, in the same year, was the establishment of Colonial Sugar Refinery (CSR), which would dominate Pyrmont for a century. The Sydney Morning Herald enthused:

Not only does the district contain a great many establishments in which hard-working mechanics and labourers earn their daily bread, but it is the domestic home of large numbers ... Its tone and atmosphere savour of toil, and it may be duly considered a home of industry over which the genius of labour might sit enthroned, and look around well pleased.

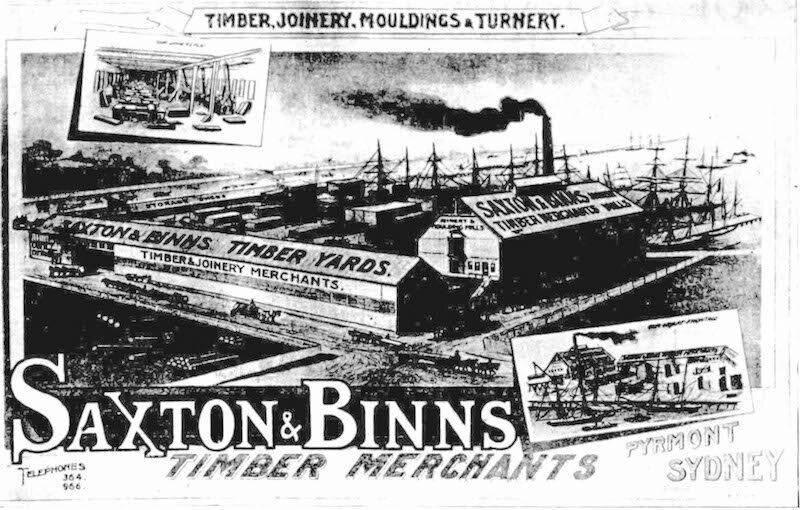

[The main industries were] works for the manufacture of machinery and ironwork, timber yards and sawmills, and stoneworks. The Government and Municipal Council are represented by the erection of the new meat market, a Public school, and road improvements.

A few years later, the Illustrated Sydney News (25 July 1889) was more realistic:

Pyrmont is not an attractive place, neither is Ultimo. As an industrial centre, however, Pyrmont is undoubtedly a place of importance, as its numerous factories and workshops abundantly testify. And Pyrmont is a perfect hive of industry, a busy bustling manufacturing centre, which produces vast quantities of necessaries, employing an army of artisans and labourers.

The shops and houses in Harris-street are … mean and insignificant. Some day they will all come down and Harris-street, a nice broad thoroughfare, will become another George-street.

At the turn of the century the Australian Town and Country Journal (October 1900) hailed Pyrmont as “a great industrial centre”. Having acknowledged the Harris dynasty and politely ignored the bubonic plague, the journal declared that Pyrmont’s prosperity was assured as water frontage, cheap land, and closeness to the city attracted new businesses alongside the quarries and ship yards.

With the passage of time, industrialism lost its glamour. In 1911, the Evening News (25 July 1911) presented industrial development as an existential threat:

PYRMONT'S DOOM

ITS PASSING AS A RESIDENTIAL QUARTER

HUNDREDS OF HOUSES TO GO

GROUND FOR RAILWAY, WHARVES AND FACTORIES

BIG SLUMP IN SCHOOL ATTENDANCES

What foresight! Palatial wool stores, railway extensions and CSR’s diversification meant property resumptions, tenant evictions and environmental destruction. In 1930 the school closed.

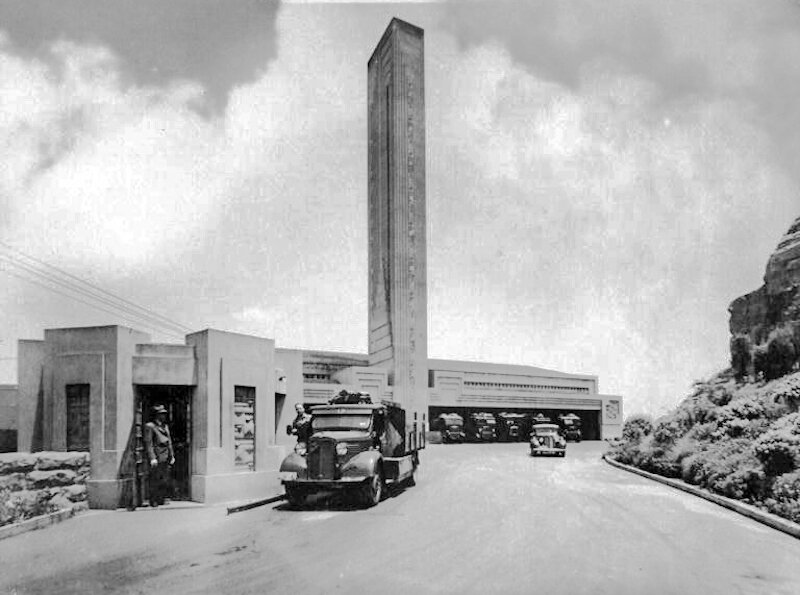

After the First World War, the industrialisation of Pyrmont meant the expansion of established processes. CSR added building materials and chemicals, wool flowed through more wool stores to Darling Harbour, and the railway system and wharves grew and were modernised. The most obvious novelty – and our most innovative - was the Burley Griffin incinerator (1937). This expansion, and the creation of car parks for commuters squeezed many families out of their cottages. Pyrmont was hyperactive during the Second World War, and some pre-war industry revived in the 1950s, but there was little new activity. The quarries closed and wharves fell silent as cargoes moved to Botany Bay; many of CSR’s processes moved elsewhere; and power stations closed.

Old industries were in slow decline. When CSR closed its Pyrmont plant, the state stepped in to plan a suite of hi-tech industries, initiating our second industrialisation with clean, quiet processes, compatible with residential towers, making this one of Australia’s most densely settled suburbs.

Hi-tech companies create no smoke and they need very different – and fewer – employees. In amongst the residential towers, industrial Pyrmont is silent and invisible.